When I woke up yesterday morning and saw the news, my heart sank. There were no headlines yet about the shooting in Fort Myers, Florida, but I was staring at an article describing how a Syrian refugee had blown himself up near a music festival in a town about an hour away from here by train. Thankfully, no one else was killed. Regardless, I knew that the idea of a refugee suicide bomber would be a major blow to an already traumatized consciousness.

Over the last week, the people of Bavaria in Germany have experienced three incidents of tragic violence: an axe attack on a regional train, a mass shooting in a shopping center, and then this suicide bombing. The details emerging suggest that the shooting had nothing to do with organized terror; the other two attacks were likely inspired by the so-called “Islamic State,” even if they were not part of a coordinated program. But what really links these incidents together is the fear they generate. They all happened in public places where there was a potential for a lot of casualties. And—let’s just say what everyone is thinking so we can deal with it—the perpetrators were all young men from Middle Eastern backgrounds. So each of these is of the sort that makes people want to push a “terrorism” panic button.

So when I read the news yesterday, I also knew that I myself needed some time to process this. How should I as a Christian respond to this violence and to the fear it generates? I decided to meditate on Jesus’ response to violence. Here are those meditations.

As I write this, I’m also very aware of the recent attack in Nice, France and of the spate of tragic violence and deep soul-searching in the U.S. over the last months, including the shooting in Fort Myers Sunday night. My thoughts below stem especially from the situation here in Germany, but I’ll leave it to you to decide how they might apply to these other situations.

The Panic Buttons vs. Jesus’ Response

I mentioned a terrorism panic button above. Actually, I think there are at least three typical reflexive responses—three panic buttons labeled “Terrorism.” Maybe there are more. (Let me know in the comments if you think so.) Here are each of them, and some reflections on how Jesus responds to each one.

Panic Button #1: Attacking the Aggressors

This is the most obvious one. In the heat of the moment, everything is out of proportion. We want not only to hold the perpetrator responsible, but also to extend that responsibility to others. Our brains simplify everything. In the same way that we perceive tables as rectangles and oranges as circles, the world after an attack becomes “us” and “them.” Groups become labels and labels become groups. Where those lines fall dividing one group from another depends very much on one’s frame of reference.

We think we know Jesus’ response of love and forgiveness. But do we?

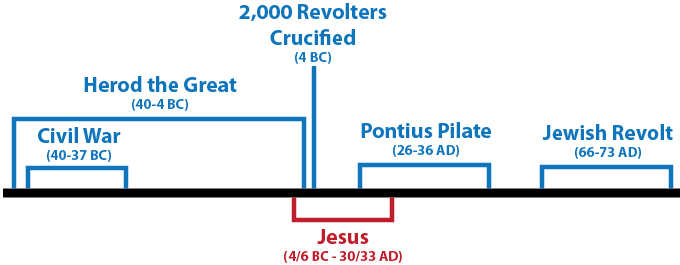

Paintings of Jesus in peaceful pastoral settings fail to remind us that violence was part of the scenery in the Palestine of Jesus’ day. His lifespan, from 6/4 B.C. to 29-33 A.D. was literally sandwiched by it. Matthew (2:16) records the cruelty of Herod the Great, who systematically slaughtered the infants of Bethlehem. This was a man who had come to power through a civil war (40-37 B.C.) and was willing to murder his wife and children in order to keep that power. Josephus records that, when a rebellion broke out after the Herod’s death in 4 B.C., the Roman ruler of Syria crucified two thousand revolters. [1] The Pax Romana was somewhat thin at the edges of the empire. Once Judea came under direct Roman rule, the Roman administrators assigned to the region had to be ones capable of nipping insurrection in the bud. Pontius Pilate was overqualified in this department. [2] Not surprisingly, there were zealots who wanted to end this Roman occupation and Messianic pretenders who rose and fell. The situation reached a boiling point in the rebellion of 66-73 A.D., about four decades after Jesus’ death, to which the Romans responded by annihilating much of the Jewish population and razing the city of Jerusalem to the ground.

When Jesus talks about turning the other cheek, forgiveness, and loving one’s enemies, these are not romantic ideals. There were bruised cheeks in the audience. Many of his hearers had real enemies.

It is easy to think Jesus’ statements are obvious and accepted almost universally in theory, even if not achieved in practice. But all it takes is a conversation with someone from a different culture or social position to recognize that these values are not universal. When justice is at stake, non-retaliation feels inadequate. When honor is at stake, forgiveness brings shame. When the upper hand can be gained or lost, revenge seems strategic. What Jesus was saying was as shocking to his hearers as his statements about money or sexual lust would be today in Western societies.

If non-retaliation is not universally obvious or accepted, then at least we in post-Christian cultures think that this panic button of aggression has been deactivated in our societies—that “revenge” is old-fashioned in this day and age—and that social progress has moved us beyond such a primitive reflex (as if the passage of time is any guarantee that we have progressed in the right direction). It is true that these cultures glorify non-violence and tolerance. But revenge is not as lost as we might think. It is too deeply rooted in the human heart to be truly gone. Politicians of all flavors know this when throughout human history they have enacted programs that capitalize on the aftermath of attacks. On a personal level, when I consider my own feelings about these recent incidents, I realize that, deep-down, I’m kind of glad the attackers didn’t survive—even though they were young men who had their whole lives ahead of them. Perhaps there could be some sort of justice in this; but, even so, I don’t have to be glad about it. The feeling reminds me of the too-familiar satisfaction of watching the morbid end of a movie villain. The revenge button is still active—it just masquerades as other things.

Moreover, those of us who are Christ-followers can mistake the generic values of non-violence and toleration for the things Jesus has actually called us to. Forgiveness, by definition, requires a giving up of certain rights. In Western society, that sounds like heresy. In the days leading up to the attacks, I had been reading Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s thoughts about revenge, based on the Sermon on the Mount, in his Cost of Discipleship. I think it is worth quoting at length. I’m still wrestling with what he says here, but I think his reflections are thought-provoking and deserve consideration.

“The right way to requite evil, according to Jesus, is not to resist it.

"This saying of Christ removes the Church from the sphere of politics and law. The Church is not to be a national community like the old Israel, but a community of believers without political or national ties. The old Israel had been both—the chosen people of God and a national community, and it was therefore his will that they should meet force with force. But with the Church it is different: it has abandoned political and national status, and therefore it must patiently endure aggression. Otherwise evil will be heaped upon evil. Only thus can fellowship be established and maintained.

"At this point, it becomes evident that when a Christian meets with injustice, he no longer clings to his rights and defends them at all costs. … [He] leaves the aggressor for [Jesus] to deal with.

"The only way to overcome evil is to let it run itself to a standstill because it does not find the resistance it is looking for. Resistance merely creates further evil and adds fuel to the flames. But when evil meets no opposition and encounters no obstacle but only patient endurance, its sting is drawn, and at last it meets an opponent which is more than its match. …

"Violence stands condemned by its failure to evoke counter-violence. … By his willingly renouncing self-defense, the Christian affirms his absolute adherence to Jesus, and his freedom from the tyranny of his own ego. The exclusiveness of this adherence is the only power which can overcome evil.” (Discipleship, trans. R. H. Fuller, 141-142)

So how does Jesus respond to violence, if not with revenge? He starts at the personal level, with forgiveness—bearing the cost of another’s wrongdoing—and reconciliation—the restoration of right relationships. Regarding loving one’s enemies, Bonhoeffer comments that the disciple’s behavior “must be determined not by the way others treat him, but by the treatment he himself receives from Jesus” (Discipleship, 148; see Mt. 6:12-15). Our response to anger, Jesus says, should be to “be reconciled to your brother” (Mt. 5:24).

Consider the disciples Jesus chose to mentor at a place and time so pervaded by violence. Matthew (Levi) the tax collector was firmly ensconced in the oppressive Roman administration and was probably resented by the fishermen in his area, including Peter, James, and John. At best, he was not to be trusted; at worst, he was a traitor. Simon “the Zealot,” on the other hand, may have been associated with the violent guerrilla revolutionaries who were trying to overthrow Roman rule. We don’t know enough about him to say for sure, but it is possible that he was a prospective terrorist. Through his life and his death, Jesus effects reconciliation among these hostile men.

Resolving anger with reconciliation is the kind of response that actually can prevent terrorism. This prompts me to think about my own relationships. Are there ones with unresolved anger? This is the very thing that can lead myself or others to perpetrate violence.

Responding to violence with forgiveness and reconciliation seems ineffective. Ultimately, I fear that my forgiveness will be run into the ground by the world’s evil, and that my capacity to forgive will be utterly expended—that I will be incapable of bearing the cost of the wrongdoing that comes my way and rushes past me, meeting no barriers. But that is an essential part of Jesus’ response to violence. He was more than an example. He himself was able to bear that cost, in his words, by being “a ransom for many” (Mt. 20:28), and, in the words of Paul, by reconciling “us both [Jew and Gentile] to God in one body through the cross, thereby killing the hostility.”

Let’s take a look at the second panic button.

Panic Button #2: Blaming the Victims

This one has two main varieties. The first is extrapolating someone’s guilt purely or primarily from the badness of what they experience. Fate got someone back, or their “karma” caught up with them. In Jesus’ days, and in Job’s, it was popular to think that bad things happening to you meant you were experiencing God’s judgment for sin, even if no one could quite identify what that sin was.

Jesus addressed this in at least a couple of places. In John 9:1-7, Jesus’ disciples ask him whether a man’s blindness from birth was caused by his own sin or his parents’. (Notice that these are the only options they suggest.) Jesus responds that it is neither, “but that the works of God might be displayed in him.” He doesn’t supply the cause of the man’s blindness, only what God wanted to do with it. Then he proceeds to heal the man.

The other incident had to do specifically with victims of violence:

“There were some present at that very time who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices. And he answered them, ‘Do you think that these Galileans were worse sinners than all the other Galileans, because they suffered in this way? No, I tell you; but unless you repent, you will all likewise perish.’” (Luke 13:1-3 ESV)

According to Jesus, we cannot take tragedies like this as a signal of God’s judgement against particular people. Rather, they are a reminder to all of us that the kind of death we should be most concerned about is separation from God.

The second variety of blaming the victims, more popular in Western societies today, is to wait for bad things to happen to people (or groups) we’ve already decided are evil or wrong. Once something does happen, our judgement of them is justified, whether or not it was really caused by what we claim. “It serves them right,” “They had it coming to them,” and “It’s their own fault” all typify this attitude. For example, mass shootings will be blamed on a population that voted against gun control, and terrorist attacks by refugees will be blamed on the people who welcomed them into their country in the first place. There may even be a measure of truth to the accusations, making them more powerful. But the problem is with the attitude.

This is a panic button for two reasons. First, it is sometimes a reflexive action rather than a deliberative response. Second, people use it to process violence. It quickly encases victim and perpetrator in one big ball of blame, severing any tentacles of responsibility that might extend to a third party (including oneself). It wraps problem and solution into a single neat package; the solution, of course, being one that could only have been implemented by the victim, and it’s too late now.

This attitude is not one of love or compassion (weeping with those who weep—Romans 12:15), but of self-justification. It does not take the spirit of “unless we repent, we shall all likewise perish.” Jesus’ words about judging are often misquoted to mean that we should not call evil evil. His instructions to his disciples clearly show that was not what he meant. (Consider, for example, that he told them to shake the dust off their feet as a testimony against a house or town that did not receive them—Matthew 10:14 and parallel passages.) What Jesus’ words do warn against is the hypocrisy of passing a sentence on someone else’s sins while failing to examine our own. (“With the judgment you pronounce you will be judged …. Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?”—Matthew 7:2-3) This is precisely what we do when we blame victims—we have determined their guilt and their punishments in our own minds, and have refused to search our own hearts for anything that might be just as evil and for which we can only humbly rely only on Christ’s forgiveness.

Finally, consider Jesus’ response of compassion in the story of Lazarus. Jesus knew what had caused Lazarus’ death, though nobody else did. He knew what he would do about it (raise him from the dead). Still, he wept.

Panic Button #3: Blaming Society

The third panic button is the converse of the second. Instead of concentrating the blame on the victims, it scatters it across society. Rather than offering idle criticism at a safe, uninvolved distance, it pretends to provide explanations or even solutions that involve all of society. Such-and-such system is broken—education or technology or immigration policy, for example. One group is too powerful, and another is under-resourced. And so on.

In the wake of the recent attacks, news sites have been quick to provide background on each of the attackers that helps their readers understand why they did what they did. The Würzburg axe-wielder was a 17-year-old asylum seeker who came to Germany as an unaccompanied minor. He had recently learned of the death of a friend and had also—quite recently and quite quickly—been “radicalized” by IS. Trauma, loneliness, and propaganda are factors in his story. The 18-year-old Munich-born German-Iranian who fired on the crowd in the shopping center had a history of serious mental illness (two months in a psychiatric hospital) and was bullied at school. The 27-year-old Syrian who detonated a backpack bomb in Ansbach had already attempted suicide twice, and his police record included drug abuse. Clearly, mental and emotional health played a major role in these incidents.

News reports such as these attempt to satisfy the “why” question that emerges from the pain and loss with explanations of “how” such tragedies came to be. These background explanations may rightly identify important factors, but none of these explanations address the root issue. As a reflection in the Süddeutsch newspaper puts it, “Traumatization, loss of perspective, and propaganda are never an excuse for murder. But they are part of the explanation.” Ultimately, people are still left searching for a coherent interpretation of the events that both points to the root causes and imbues the tragedies themselves with some kind of significance.

Blaming society, environmental factors, and so on functions as a panic button in two ways. For one, it finds an immediate home for the blame in large-scale social dynamics, which are complex enough and abstract enough to be factors in just about anything. Some of this blame may even be converted to guilt—self-blame—which can be a strangely satisfying way to reduce unknown factors into ones we can understand and control. For another, it dangles before us the thread of hope that we can actually remedy the situation ourselves if we simply fix this or that problem. I personally find this button the most tempting response. But it is a false hope. So long as we are only repairing society and not restoring the people in it, the social “malfunctions” that still need to be rectified will be endless.

Jesus lived in a society with very broken systems. The Roman authorities were oppressive. Philo accused Pilate of “continual murders of people untried and uncondemned” [3], not to mention the daily abuses of power perpetrated by Roman soldiers and tax collectors (see Luke 3:12-14). The Jewish high priesthood (think national civil government) was utterly corrupt and concerned about keeping their own wealth and power at all costs. The religious scholars and lay leaders loaded people with moral burdens which they themselves were not willing to lift a finger to help with (Matthew 23:4). Amid all this, Jesus did not hesitate to point out injustice. Yet, so far as I see (tell me if I’m wrong!), he always did so by addressing the wrongs of the people within those systems, whether they were scribes and Pharisees, priests, temple merchants, or tax collectors. Instead of vaguely blaming broken systems, he recognized the root issue: “Out of the heart come evil thoughts, murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false witness, slander” (Matthew 15:19 ESV).

Here’s Bonhoeffer again. He’s continuing on the theme of loving one’s enemies, but he’s also touching on the issue of social evils and injustices:

“We are concerned not with evil in the abstract, but with the evil person. Jesus bluntly calls the evil person evil. If I am assailed, I am not to condone or justify aggression. Patient endurance of evil does not mean a recognition of its rights. That is sheer sentimentality, and Jesus will have nothing to do with it. The shameful assault, the deed of violence and the act of exploitation are still evil. The disciple must realize this, and bear witness to it as Jesus did, just because this is the only way evil can be met and overcome. The very fact that the evil which assaults him is unjustifiable makes it imperative that he should not resist it, but play it out and overcome it by patiently enduring the evil person.” (Discipleship, 142)

Of course we should work to correct systems that allow and encourage injustice, abuse of power, marginalization, and so on. But the point is that explanations and solutions on these levels will never go deep enough. Behind each “how” question lies a “why,” and behind each “why” lies another “why.” Ultimately, we either spiral in a vicious circle of unanswerable questions, or we end up addressing our “why’s” in pain to the one the philosophers call the “First Cause,” God himself. As Job experienced, God may never answer that question. But at least we will have collided with someone full of compassion, who will act for good in every evil situation.

Conclusion: The Beatitudes

Several of the beatitudes seem especially appropriate to recent events:

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. … Blessed are the merciful, for they shall receive mercy. … Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.” (Matthew 5:4-5,7,9 ESV)

These sayings are not beautiful principles. Jesus is proclaiming that he, as the Messiah, is enacting his redemptive program. They are a call and an encouragement to Jesus’ disciples to follow him.

Each of the above panic buttons is an immediate response to blame someone or something and to prescribe a program based on that blame. As I think about and talk about tragedies such as these, I pray that I will guard against each of these faulty responses. Jesus’ response makes me acknowledge the evil within myself, the cure that only he can provide, and the call to follow in his footsteps.

1. Note that historians generally think Josephus exaggerates numbers.

2. See Paul Wright, Greatness, Grace, & Glory, 199-208.

3. Wright, 202.

Header picture from theguardian article